WLP358 The Birth of Telework: A Persistent Quest for Change

Have you ever wondered who first came up with the hypothesis that knowledge workers could do their work together, but from separate locations? In today’s episode, Pilar talks to Jack Nilles, who not only ran the first experiment in “telecommuting”, but also came up with the word! Thanks to this very persistent physicist, we now have a new way of working that has changed the lives of many.

Today’s show notes are a little bit different. We’d like to keep Jack’s story in his own words as much as possible, so we’re sharing a polished version of the transcript.

Jack takes us on a journey through the very early days of telecommuting, sharing the challenges and triumphs he experienced while pioneering this new concept. From convincing skeptical companies to adopt telework to exploring the societal benefits of reduced traffic congestion and pollution, Jack's story is a fascinating glimpse into the birth of a movement that continues to shape our world today.

But before we get into the conversation, here are a few links you might be interested in:

Jack’s blog, JALA’s thoughts: https://www.jalahq.com/blog/

Jack features in the film WORK DIFFERENT, which you can watch online: https://www.nfb.ca/film/work-different/

JACK: Good afternoon, good morning, good evening, wherever you are. I'm Jack Nilles.

PILAR: Welcome, Jack Nilles. This is a bit of a spoiler for everyone listening who hasn't come across your work yet. Jack, am I right in saying that you were the person that came up with the word telecommute and telework?

JACK: That's exactly right. 1973.

PILAR: Wow. And I am looking forward to hearing about why and how you came up with those terms. So let's just start with the very beginning. I understand that you started your professional career as a physicist, even at one point consulting for NASA, and that you later joined the University of Southern California as director for interdisciplinary research in 1973. And around then, you published the telecommunications transportation trade-off. And you're, of course, also the author of Making Telecommuting Happen: A Guide for Telemanagers and Telecommuters and Managing Telework. And you are the president and co-founder of JALA, which is dedicated to involving telework as a central change agent for satisfying major strategic goals. So let's start at the very beginning, at the beginning of your career.

JACK: My first career was as an officer in the United States Air Force, and then later with the Aerospace Corporation, the engineering background for the Air Force space program. I consulted with NASA to help them select the cameras to use to map the moon so they could figure out where to land the Apollo landing vehicles. As part of my work in the aerospace program, it was all very highly classified, and I got really tired of that. I said, you know, what can I put on my resume? What did you do? Well, I worked for 15 or 20 years for this company. Yeah, but what did you do? Nobody will tell me.

I was looking around for some other way, some place else to do something different. So I said, well, let's ask people in the civilian world about how we can use our technology to help them. I came across an urban planner who said to me:

““Well, if you people can put man on the moon, why can’t you do something about traffic?””

That's a really good idea.

So I got really interested in this and started to think about how you could use the technology to reduce traffic. You think about the fundamentals. Generally, the reason we have traffic jams is that people get in their cars by themselves and they drive to work someplace, and half of them are driving to an office somewhere.

And what do they do in the office? They pick up their phone and talk to somebody else somewhere else. I said, why did they have to go to their office to do this? Why can't they just do it at home? And that began the thing. I got really intrigued by this, and I was the secretary of the corporate planning committee, and I said:

“Hey, guys, why don't you support a little experiment having our people work at home, or at least some of them? We want to find out what the effects of this might be. Well, what would it take to calibrate it? Well, we'd probably have to hire a lawyer or two and maybe a sociologist and some psychologists.”

And they said, forget about it. We're engineers. We don't deal with this touchy-feely stuff. So I was really mad about this, and I was complaining to a friend of mine at the University of Southern California and he said, “Well, why don't you come here and do it?” So that's the long story from my transition from being a rocket scientist to being a director of interdisciplinary programs at USC.

But one of the first programs I wanted to work on was, and I'll give you the title of the project, was “the development of policy on the telecommunications transportation trade-off”. We got a grant from the National Science Foundation to do this, and the first thing I did is say, “Look, people will fall asleep just listening to the title of this work. I have to think of something catchier.”

I came up with “telecommuting” because the first emphasis is to reduce the commute to work to zero in many cases. But employers, they're interested in work being done. So I said, let's also call it “telework”, because that pleases the employers, and telecommuting pleases the commuters. So either one works, depending on what your attitude toward this is.

“I came up with “telecommuting” because the first emphasis is to reduce the commute to work to zero in many cases. But employers, they’re interested in work being done. So I said, let’s also call it “telework”, because that pleases the employers.”

PILAR: Wow.

JACK: Anyway, we tested it out, so...

PILAR: One second, Jack, because there's so much in there that I want to ask you before we go into testing. So you said the technology was available. What technology was there for people to be able to work from home then?

JACK: It's called: the telephone.

PILAR (laughing): They don't have any of those anymore. No one uses it now. So I'm really glad to hear that, actually. The telephone is a very powerful tool.

JACK: Yes, that's right. So, in 1973, the technology that people used to talk to each other vocally without sending them a text or anything was a telephone. But if they were working with computers, as most of the people in our experiment were, the telephone was not technically competent. It couldn't handle the bandwidth needed to send data back and forth instantly as they were working.

We set up our experiments so that we were putting people not working from home, but in satellite offices near where they lived, so they didn't have to get in their cars to get to work or take mass transit or whatever. They typed into a mini-computer at that center. So it was collecting all the data. They would type at higher speed than the phone line could handle, and then at night, the computer would send all the data up the line to the company's mainframe, which is in downtown Los Angeles. There are always easy technological ways to get around most of these problems, which has always made me say that technology isn't what's inhibiting telework. It's the problem between managers' brains - that’s the problem, not the technology.

PILAR: So if I understood correctly, it was a mixture between the people working from home and using the satellite offices, the setup for the experiment. Wonderful. Okay, nice. So you were actually looking at different things in there as well. From our eyes now, you were almost like, can we give people offices near to their homes and support and supply their homes?

JACK: Yeah. Because, you know, by then, the personal computer had not been invented or at least not put into production anywhere. That didn't happen until, like, 1981, when the IBM PC came out. So here was between 1973 and 1981, we were still in this mode of having people work in or near satellite offices or something like this that communicated with the company mainframe.

PILAR: Good. Let's carry on. From where I stopped you.

JACK: The experiment was a success. We ran it into 1974. Productivity went up by 15% for the people. And the thing that impelled the company to take us on in the first place. Oh, by the way, I should point out, I wanted to work with an actual, real live company, not tested on graduate students someplace, a biased sample. So we wanted to work with a real company, with real employees, and see what happened. Anyway, it was a big experiment. Productivity went up. We figured if the company made this available to much of their staff, their space savings and the turnover rate, they were experiencing one-third of their staff would disappear every year and they'd have to hire new ones. That's expensive. Turnover rate went to zero.

PILAR: Wow.

JACK: Space savings went up considerably. Productivity went up. What's not to like? We figured they would save four to $5 million a year if they had this full-time for their employees. Great, companies, this is wonderful. We're not going to do it, right? Why not? Well, we're a non-union company, and we figured if we have these satellite offices scattered around, why, the union can come in and organize them one by one. And then at some point, we'd be forced to be a union company. So we're not going to do it. A couple of months after this meeting, the project's over.

A couple of months later, I was meeting with the chief planner, the strategic planner for the AFL-CIO, the big labor union organization in the United States, and I told him about telecommuting. He says, oh, that's a terrible idea. I said, why? He says, well, if your employees are scattered all over the place, how will we ever organize them? The company didn't like it because it was too easy to get organized. Unions didn't like it because it was too hard to get it organized. This is the kind of management and distortion that has plagued it ever since.

PILAR: Yeah. It's also that fear, I think, for me, what I'm hearing, I'm trying to get into the skins of all these people, thinking, what on earth is this guy talking about? How are we going to do this? This is going to be so much work. I don't know how to do this.I think a lot of the time, the people in charge don't know, for whatever reason, and because we don't know how to do it, we're very afraid. And it's a huge change.

JACK: Absolutely. This is a major culture shock, as we have spent the last 50 years trying to show. But it really is. I mean, my sequence usually of getting a company involved in this is to start, say, at time zero, get in to talk to the president of the company, the CEO, and explain what all this is and how it really works. And here's some evidence we have that it works for real companies, the real world. Maybe not your company, but your company is close enough to these that you can do it. And they say, well, okay, after six or seven months, we can talk to some of the mid-level managers and we have to explain the whole thing all over again to them. And so finally, after roughly, on average, about two years after that first meeting, the company says, okay, let's try it. To be in this business, you have to be really patient.

PILAR: Yes. Yeah. This has been the problem, I think, with the pandemic is that it was such a rush and we know, and we knew that this just takes so long because of all the, like you were saying, the psychological and sociological change.

JACK: The other crucial thing once you finally start, we were very careful to make sure the company's rules and procedures were okay, that all the legal questions they worried about were okay with their lawyers, that we had work procedures set up properly for all the technologists to make sure it was possible to provide the proper technology to let people work remotely and so forth. They got all this ready. Then we started training people, explaining first to the potential telecommuters what this was about. Here's the idea. You work at home, but that doesn't mean you don't have to work. You still have to work. You can't watch television and play with the kids. You have to get the work done, but not necessarily during normal working hours, when it suits you. And they say, that's interesting.

We talked to the middle managers, and these are the hardest bunch. No, your job won't go away. You're still going to be needed, but you're going to have to become a leader instead of just the accountant to make sure everybody's looking busy, because, as Tom Peters used to say, you know, well, he was afraid of management by walking around. I said, Tom, you can't walk around because they're not there.

PILAR: What did he say to that?

JACK: He grumbled. He says, well, yeah.

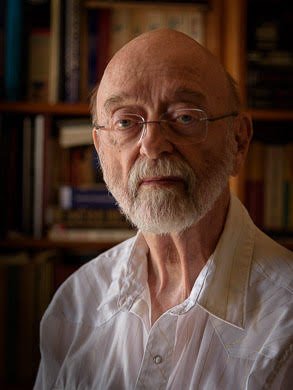

Jack Nilles providing training for UNED Costa Rica

14.55 MINS

PILAR: So, Jack, what happened then? Between, out of curiosity and wanting to solve a problem, you set up this experiment with the company, you showed the benefits. And then they said, in all sorts of ways, no, what did you do then? How did you get from that experiment to helping companies. What happened with your career?

JACK: I tried to get support for more experiments because it's just one company and I want to set it up so that we could prove this for diverse sorts of companies, not just an insurance company. Everybody knows they do paperwork, but, yeah, what other kind of company? It's possible for this to happen. So I thought, well, let's try to get some federal support, because if we can reduce traffic, that's something. So I went to the Department of Transportation. I thought, hey, I've got this system of reducing automobile use to cut down on all the traffic jams we have because people would be working at home instead of getting in their cars and clogging up the freeways. And he said, no, no, no. You don't understand. Our mission is to make automobiles more efficient and traffic flow more efficient, not to get rid of it.

PILAR: Why would you want to do that?!

JACK: So then I went to the Department of Energy and said, hey, look, you may not realize it yet, but energy is going to be a major global problem because we're using these fossil fuels. We're digging up fossil fuels at a rate that the atmosphere won't be able to withstand it. So what I want to do is get people out of their cars, because traffic by cars, automobiles in 1973 was about 24, 25% of the air pollution, all the carbon dioxide going in the atmosphere. So I said, let's stop this. We have to stop it sooner or later. That message clearly still hasn't gotten through yet. And we had to cut down use of fossil fuels. And I said, no, no, no, you don't understand. Our job is to make internal combustion motors more efficient, not to get rid of them. This is before EVs were lightening up everybody's mind. And agency after agency after agency, I went with, they all gave me, this is not our mission. Our mission is to make x better instead of doing y, which is sort of at an edge of what we do. And then I got a few more companies involved in this.

And this lasted through the early eighties. Lots of proposals, lots of rejections. But I've discovered how stubborn I can be. After a while, I kept at it. And then around 1984, we finally got together a coalition of Fortune 100 companies at last. And they all supported another set of experiments. In each company, I do this, and sure enough, it worked. So we had major, you know, Fortune 100 companies were involved in telecommuting, and it worked for them. There was only one hitch. Well, you can say it's good, but you can't mention us in what you say about it.

PILAR: So it was great, but we don't want our name associated with it, right? Wow.

JACK: I mean, if I have this new method where all I have to do is buy a little bit of technology and train people to work differently and save all this money, cut down my expenses enormously, why should I tell my competitors about it? Okay.

PILAR: Wow.

JACK: So anyway, so that was another great experiment, I could say. I mentioned we did this great thing, and they say, well, who'd you do it with? Never mind. We did it with big companies, All right. 1985, thereabout 84, a fella came to me named David Fleming, who was working with the general services department of the state of California in Sacramento, and he said, I have this problem. I'm trying to figure out how to take care of an expanding workforce, and we don't want to use any real estate to do it. We just don't have office space for them. And I read about this someplace, so can you help us out? And I said, ah, a chance to do this where I can tell people what the results of the experiment were and tell them who it was with and so forth.

So over a period of, you know, from that time on through most of the 1980s, we did a preliminary study of how we would do this again. I made sure we involved many different departments of the state. So you could say, it only works for these guys, not those guys. No, it works for everybody. And so we put together a proposal and it inched its way through the process. And we finally implemented a program, trained several hundred state employees from different places around the state. The program was a great success, and we could talk about it. And one of the interesting, sort of completely unplanned fewer events was the Loma Prieta earthquake about the middle of coastal California. And the state of California had a planning office in downtown San Francisco. And the earthquake damaged that office enough that it shut down. And nobody could work in the office for about two weeks except the telecommuters we had trained, who were right on working from home. Ha ha. But still, their experience. This kept going on and on. I had more companies kind of inching their way in this, but don't tell anybody about us. The state program was over around 1990, and we did another one with the city of Los Angeles. And same results. Surprise, surprise. You know, it works for everybody. Except after this success, the population of LA elected a new mayor who was old-time, everybody in the office. They cancelled the program.

PILAR: Wow.

JACK: And other corporations that we wanted to start a program with, we get it going, and it works successfully. We're about to spread it out. They change presidents of the company, typically a lawyer or somebody from the old industrial days, and says, no, no, no, we can't do that. This is crazy. Never mind. We show it works. Don't bother me with facts. My mind is made up. We're over. What's the magic number thing we can use to really get people's attention? Saying, this is serious, it has major side effects beside your company doing better as a result of it. If we cut down pollution, if we cut down fossil fuel energy use, there are lots of benefits that you're not even thinking about yet. And I couldn't come up with it until finally the answer came. Pandemic.

23.30 MINS

PILAR: Let's pause again because I have so many questions. Again, one is a reflection of how we were saying earlier when you first, that your first experiment, how you needed lawyers involved, you needed the person who were going to support with the technology, you needed training. It's a big collaborative effort, introducing remote work.

JACK: And then COVID comes in, all of a sudden everybody is thrown out of their office. Most of them have no experience with doing this. They don't have no idea what they're doing. I thought, oh, God, yes.

PILAR: What are we doing now? Because, you mentioned this is not for everyone. Not all the jobs can be done, but there are wide benefits. I mean, of course there's also drawbacks, but we focus on the benefits. There are also wide benefits to society, to the economy, to people's lives that go beyond people being able to work in their pyjamas. So it's really like a big imagination exercise, actually could expand beyond us.

JACK: Yeah, but. Well, did you get a chance to see the documentary?

PILAR: I did. I did. And before we go into that, so the documentary is called Work Different, and I'll put the link in the show notes. It's on the National Film Board of Canada's website. Carry on. https://www.nfb.ca/film/work-different/

JACK: It's a great show of tunnel vision, people. I only worry about my job. My job is doing this and not doing crazy experiments for other people. Yeah, well, but that's nice, but not going to fix my paycheck. It's a problem.

PILAR: Yes, it is very, very tricky. And especially the whole pandemic thing was survival as well. We were all on survival mode. But I've got one question before we go from that, because I think that's very interesting as well. So you mentioned that part of the experiment was giving training to the people who were going to telecommute. Now, a lot of the training now, or a lot of the focus of the training now in 2023 is around the technology. But the technology then, I imagine, wasn't as complicated. What did the training involve of the people you were working with?

JACK: It involved thinking, reevaluating your point of view about work, about how it's done, who's responsible for what, how do you make sure it's happening? How do you evaluate the results? Our training had almost nothing to do with technology. This entire period. Technology has never been the problem. You can always find IT guys who'll set up damn near anything you want to do with it. And it gets so simple now. Everybody, at least new employees, young kids, know all this stuff. That's not an issue. So you don't train people to use the technology. They already know it. In the early eighties, maybe they didn't, but that training we left to somebody else. We trained them on thinking about managing yourself and other people and communicating with each other properly and frequently so that everybody felt included, not remote and together working with each other. And it works. And I've had managers come up to me after they've been at this a while and said, I had the totally wrong idea about this when we began with, I thought, oh, God, now they're going to put another management burden on top of me.

And I say, look, our management technique is to relieve you from being the cop, making sure the people are working, forcing them to get the work. Our emphasis is on motivating the people to get the work done in the easiest way for them to do it and working with each other appropriately. And I said, yeah, it works. Everybody comes up years, maybe later: You changed my life.

“Our management technique is to relieve you from being the cop.”

But when COVID hit, I thought, man, it's going to be a disaster that all these people swung into this overnight. No idea how to manage this stuff, but most of them have managed. You know, there's still a lot of people struggling with this. But people, given the motivation, like, you go to the office and you're going to die, they learn a lot faster.

PILAR: Yeah, yeah. Were you helping? Were you working with companies during the pandemic where you, do you still work with companies? What's your relationship now with the world of remote working?

28.55 MINS

JACK: I have not worked with any companies during that or since the pandemic. I am actually more concentrated now on the broader picture of global warming. Telecommuting is an important part of it, but there's lots of other topics managers have to get their heads turned around for. With global warming, now people are starting to notice it's real. In 1970 they said, what are you talking about? But now people are beginning to notice and saying, why doesn't somebody do something about this? And I'm trying to get people to know, you know, who's going to have to do something about this? You. You're going to have to start thinking about life differently. Your objectives and how you're using the material universe, fossil fuels particularly. You got to get yourself unleashed from the oil companies because they're going to be tools for global suicide. I won't be alive then, but don't say I didn't warn you.

PILAR: Well, already back in the seventies, you were saying, I know a solution to this, one of the many. And it took a while to get that. And the world en masse takes a while to catch up to a lot of these things.

“ In 1970 they said, about global warming, what are you talking about? But now people are beginning to notice and saying, why doesn’t somebody do something about this? ”

PILAR: I'm really interested in what you think of the new generations who were born into a completely different world of work. So, for example, I'm thinking of, in fact, in this documentary, I think it was, there was mention of young people struggling at work. They need more to be around other people. I'd like to hear your take on this, sometimes I think that this is being seen through the lens of someone whose career went like that, like my generation as well, going into an office. But with your crystal ball changing how we work, not just for the better of work, to solve other problems, how do you see the younger generations handling that?

JACK: I think they'll do a lot better at it than I have because there will presumably be less resistance to their doing it.

But there is one point that I do make. It is probably necessary for a young new employee who's never been in the workforce before to be in an office with other people for some time to get acclimated to the way companies work. You know, who talks to who, what's the gossip method here? And if I have a problem, who do I call? This sort of stuff. And that needs a certain amount of face-to-face interaction. I wrote a blog on this a couple of months ago, what you need to be successful, and another one later says what you should not use telework for, and that's new employees need to have some orientation time for maybe as long as three or four months, not forever. https://www.jalahq.com/blog/defining-the-edges-of-telework/

PILAR: Okay.

JACK: Once they figured out how the company works, how they get to know a few people, know who does what and who does what and to whom, and get a feel for it, then you've got the technology for them to still keep in touch with each other. Also, when you come to crisis times, such as developing a new project, what are we getting organized basically to head off in some other direction. You probably need some face-to-face time in the same facility deciding what we're going to do and who's going to do what. Setting up the organizational structure after which everybody go off and do their work and don't have any more meetings. Those are counter-productive anyway.

PILAR: I think you make a very good point that actually I hadn't really thought of, which was that I always think that schools are not just a place to give young people information, but it's the place where they start to socialise, as in where socialisation takes place and they learn to get on with others. And then, to your point, if you then go into the workplace and you have people around you, you're learning now to operate in society where you're not with your peers, where there's people of different generations, where you start to come across hierarchy, and that we'll see. But at the moment, it's definitely easier to do that co-located in person. It's definitely faster, and it requires less of it to be driven by the individual. And when you've got a young person, I think we need to give them more support.

I think that the online space needs so much deliberate action and self-directed action that if we're bringing people into the workforce, a good level of face-to-face, in-person contact is necessary, not just for their job and for them to learn the jobs, but for them to start to operate in this new stage of their life.

JACK: Right? Actually, I do not recommend people working from home full-time. And we mapped this. Productivity goes up with the amount of days per week you're working at home until Wednesday, Thursday, and then if it's more than three and a half, four days a week, it starts going down. I never expected early on more than about four or 5% of people would be full-time home-based teleworkers. Did a survey of the United States in 2000, and that number went up to 8%. So it's twice as what I thought originally, but still it's a relatively small number of full-time workers. The problem people are having now is trying to sort out what that number is, is the best for your group, your company, whatever, how many days at home, how many in the office, how variable is this? And so forth. So that's a period of adjustment, and I figure that's going to take two or three years still, probably.

PILAR: Well, I'm still hoping that having accepted that it can happen, having accepted that people can work away from the office and still do a good job, having accepted that there is a variety that will get all this wide range of options so that people can adjust and adapt and find a better, better fit, at least to their work location.

JACK: When we tested these projects, we always had a control group, telecommuters and their coworkers who have as identical jobs as possible to them. And we compare the two at intervals throughout this thing. And aside from their productivity, the teleworkers feel more creative, less stressed. Their medical bills go down. Okay. Clearly, clothing and eating and eating bills go down, you know, when they're not working near restaurants downtown, which is a problem for restaurants downtown, because emptying office space is now settling down to about 30% to 50% of what it used to be. Yeah, that is a problem. But cities are starting to adapt and they're converting some buildings into housing and so forth. So this is a long process. It took me 48 years for COVID to happen.

PILAR: I think it hit at a time when the world kind of could cope with it in the best way possible for that.

This is amazing. I mean, in a way, it's really interesting to hear. For me, you're like the first remote work advocate. You know, we can call it telecommuting, but for me, having been in this bubble of people advocating for remote work, I hear, I don't know if this is good or bad, but I hear your stories and I'm like, mm hmm. Only you stuck in there and you hurrahed and championed for a very long while without the world giving you some kind of: “It could happen.” The personal computer and of course the Internet and wi-fi at least made people be able to kind of see how this could happen. But when you started, it must have been very difficult to imagine that.

JACK: Well, I have a vivid imagination, so.

PILAR: I don't know, blessing and a curse.

“People tell me they want to be a consultant in this. I said, well, there are two requirements. One, persistence. You need to be really persistent. Two, you need a day job because you’re not going to live off this kind of thing.”

PILAR: Jack, I am amazed at what we've covered. I mean, we could cover things for a while.

JACK: I told you you'd have a problem shutting me up once I get started.

PILAR: No, it's delightful. That's exactly what we like. Is there anything else that you want to share about your journey? Our journey seems like it's not strong enough, but your persistence through telecommuting, from picturing in your head how this, you know, what this world could be like to then advocating and then to where you want to go next. Is there anything else you'd like to share with me and our listeners?

JACK: I used to read as a kid a lot of science fiction. And the more I got into this both in the air force, and this is that science fiction is not even close to what reality is if you change it properly, and it is up to each and every one of us to change things in a way that will benefit not just us, but the rest of the world as well. Otherwise, I mean, there's no place to go to from here, Elon Musk notwithstanding, you can't move all of us to Mars. And it's a hostile environment anyway, even more hostile than we're going to make it here.

PILAR: And I wouldn't want us all to go to Mars. We'll destroy that as well.

JACK: If there were Martians, they've already done a pretty good job of it already.

PILAR: Great. Well, listeners, I recommend that you check out, well, the documentary that Jack was referring to, which is called Work Different. It's in both French and English, so it's got subtitles, about 50 minutes long. And I think it's a good advocate tool because it covers the resistance and the advocacy, and it covers the minute personal detail and the broad sociological. Yeah. How did you get involved in that documentary?

JACK: They called me one day and I said, do you want to do a documentary on this? I said, why not? I'm retired. Right?

PILAR: Yes. Did you learn anything from that documentary and from either working on it or watching it that maybe struck you?

JACK: Well, in the nineties, my wife Laila and I spent a good part of our time commuting to Europe and Asia, telling people what a great thing telecommuting was. And I found basically the same attitudes on the part of managers everywhere. In Europe, Japan, in Australia. It's all the same kinds of resistance. It's a human characteristic. Never mind what language you're speaking, what society. Everybody is afraid of change. Show them that change is not bad if you do it properly. And the documentary was just a good example of how that process flows. People say that's possible. And finally, you edge them along and they say, hey, this may not be so bad after all. And this is.

Keep at it, fellas!

Get in touch with Jack through his website (you can email him from there) https://www.jala.com/

Jack’s blog: https://www.jalahq.com/blog/

WORK DIFFERENT, the documentary https://www.nfb.ca/film/work-different/

If you like the podcast, you'll love our monthly round-up of inspirational content and ideas:

(AND right now you’ll get our brilliant new guide to leading through visible teamwork when you subscribe!)